Financial Inclusion: Microfinance, Agency Banking, Mobile Money, Credit Bureaus, and Islamic Banking

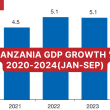

Following the financial liberalization in the ’90s to sustain the country’s economic growth, many new lenders and other financial institutions have entered the Tanzanian market.

Consequently, Tanzania has recorded significant growth in the level of financial inclusion in the last decade. According to the FinScope Tanzania 2023 Report by the Financial Sector Deepening Trust (FSDT), a program aimed at increasing financial inclusion in Tanzania, the percentage of adult Tanzanians who access formal financial services stands at 76% of adults in 2023. This is a significant 11% point increase from 65% in 2017 when the previous FinScope report was released.

The notable increase was mainly attributed to the high adoption of digital financial services, increased awareness of financial products and services, and strong collaboration amongst public and private financial inclusion stakeholders.

Nevertheless, the expansion of mobile money services has been the primary driver of growth, with adoption rates among adults increasing from 60% in 2017 to 72% in 2023. The utilization of banking services remains modest, rising from 17% to 22% between 2017 and 2023.

Conversely, the utilization of other formal non-bank financial services, such as microfinance and Savings and Credit Cooperative Societies (SACCOs), has remained relatively stable, with rates staying at 8% in 2023 (compared to 7% in 2017) and 1% (compared to 2% in 2017) respectively.

This is why Tanzania’s third National Financial Inclusion Framework (NFIF) 2022-2028 places emphasis on addressing persistent barriers and gaps, with a special focus on expanding the usage of financial services to disproportionately excluded population segments and access to and usage of a broad range of affordable financial products and services for financial health. The objective is to have all Tanzanian adults and businesses have an account with financial service providers (FSPs).

In addition, the Financial Sector Development Master Plan 2020/21-2029/30 states that financial inclusion is imperative in the drive toward the achievement of economic growth, poverty reduction, and financial sector stability. For this, the Government has taken several initiatives including the development of the National Microfinance Policy 2000 and the First Financial Inclusion Framework 2014-2016 which provided for the establishment of the National Council for Financial Inclusion, comprising members from both the public and private sectors.

Despite the achievements made, the Plan highlights challenges that financial inclusion still faces:

(i) High cost of financial products and services: Financial services in the country are expensive due to low levels of competition, infrastructure constraints, information asymmetry, non-performing loans, and enforcement of creditors and debtors’ rights;

(ii) Limited access to financial services: Access to formal financial services in the country is

still low with 24% of the adult population financially excluded;

(iii) Most enterprises, particularly MSMEs, remain underserved by the formal financial sector: Most MSMEs are informal, hence they cannot access finance from financial service providers. This is attributed to strict KYC requirements and formal registration, collateral, credit history, and lack of MSME-tailored products;

(iv) Social norms: Certain socio-cultural norms prevent sections of the population (particularly women, youth, and disadvantaged groups) from accessing formal financial services and products; and

(v) Inadequate legal and policy environment to foster innovation: This hinders the development of appropriate products and models that offer effective solutions for consumers.

Microfinance

Microfinance refers to the provision of financial services to low-income individuals who are traditionally not served by conventional financial institutions. Most microfinance institutions focus on offering credit in the form of small working capital loans, sometimes called microloans or microcredit. Microfinance is globally acknowledged and accredited for its role in fighting poverty as evidenced by many countries that use it.

Microfinancing in Tanzania started in the ’90s with savings and credit cooperative organizations (SACCOS) and NGOs. The microfinance sector came to serve a large portion of the population who would not have had access to credit and finance otherwise. While this has had a significant impact on the economy, a lack of regulation has left the sector vulnerable to financial irregularities and the target of fraudsters and money launderers.

In recognition of the potential of the microfinance sub-sector in poverty reduction and economic growth, the Government of Tanzania formulated and adopted the first National Microfinance Policy in 2000 (NMP, 2000).

The Policy was reviewed in 2017 by formulating the National Microfinance Policy 2017 (NMP 2017) and its implementation Strategy for the period of ten years from 2019-20 to 2029-30.

The main objective of NMP 2017 is to promote financial inclusion by creating an enabling environment for an efficient and effective microfinance sub-sector in the country that can serve the needs of individuals, households, and enterprises on low incomes and thereby contribute to economic growth, employment creation, and poverty reduction.

In addition, the Government enacted the Microfinance Act of 2018. BOT has been mandated to license, regulate, and supervise the microfinance business in the country.

Tanzanian Microfinance Banks

In addition, the Government enacted the Microfinance Act of 2018. The Act classifies microfinance service providers in four tiers:

- tier 1 – deposit-taking microfinance service institutions (DTs) such as banks and microfinance banks;

- tier 2 – non-deposit-taking microfinance service providers (NDTs) such as individual money lenders;

- tier 3 – savings and credit cooperative societies (SACCOS); and

- tier 4 – community microfinance groups (CMGs).

According to the latest information of 2023 made available by BOT, there are in Tanzania 3 microfinance banks, (Tier 1 microfinance institutions), and 1,352 Tier 2 microfinance institutions.

The microfinance banks are AccessBank Microfinance Bank, Finca Microfinance Bank, and VisionFund Tanzania Microfinance Bank. In 2022, their total assets accounted for 0.4% of the total assets of banking institutions.

Challenges Faced by Tanzanian Microfinance

-Management Information Systems: Most of the microfinance institutions (MFIs) have inadequate capacity to collect statistical and other relevant information regarding their operations as well as insufficient capacity to develop Management Information Systems (MIS);

-Lack of central credit information register: The lack of a unified central point for sharing and verifying client credit information has exposed the microfinance clients to multiple loans;

-High interest rates: Microfinance institutions in the country charge high interest rates based on the cost of capital, personnel, administration, and loan loss. It is estimated that administrative costs amount to up to two-thirds of interest paid by clients. Some of MFIs charge significantly high effective interest rates ranging from 3 to 20% per month.

-Inadequate working capital for microfinance services providers: Most of the MFIs have inadequate working capital resulting from the poor saving culture of members and the inability to secure affordable and reliable financing sources; and

-Weak institutional capacity of microfinance service providers: MFIs face a set of inter-related challenges, such as limitations in the scale of their operations in terms of outreach and number of clients served; poor portfolio quality; limitations in their professional capacity; weak governance structure; poor accounting and record keeping; inefficient operations; and, lack of financial discipline.

Nonetheless, the increase in the number of microfinance providers is a manifestation of the growth of this segment. Julius Ruwaichi, CEO of Selcom Microfinance Bank Tanzania, explains that his company is experiencing significant growth rates, prompting expansion into various segments of the Tanzanian population. He states, “We are extending our services into new markets, with a primary focus on becoming the preferred one-stop bank for micro, agro, and small enterprises. We are particularly dedicated to expanding our market share by serving the lower and middle-income strata of Tanzanian society.”

Housing Microfinance

Furthermore, micro mortgages also present opportunities. Tanzanian housing demand is estimated at 200,000 houses annually and a total housing shortage of 3 million houses.

The 2023 Housing Microfinance (HMF) in Tanzania report by TMRC identified that depositing and withdrawing savings was the most popular financial service used by respondents. Borrowing was nowhere near as popular, and respondents tended to pay for unexpected expenses out of their savings, or by borrowing from family or friends, rather than taking out a formal loan from a financial institution.

The TMRC study assumed that the most suitable target borrowers for HMF products in Tanzania are low- and middle-income households who earn between 80,000 TZS (USD 34) and 1,500,000 TZS (USD 630) per month.

If they did borrow, respondents would generally prefer to do so with a commercial bank, community finance group, or their family and friends, rather than a microfinance institution, savings and credit co-operative society, or their employer. A good interest rate, bigger loan size, and efficient lending process were likely to be major factors in determining the choice of lender. Most respondents would prefer to limit monthly loan repayments to the 5,000 to 80,000 TZS range.

Meanwhile, on the supply side, financial institutions in Tanzania showed a lack of awareness of housing microfinance, particularly regarding how it differs from “traditional” housing finance products like mortgages, low levels of technical capacity, and lack of long-term, affordable funding, thus hampering the expansion of HMF.

In conclusion, housing microfinance in Tanzania holds significant potential to address the country’s housing shortage and meet the financial needs of low- and middle-income households.

Banking Network and Agency Banking

Banking services are offered through various delivery channels which include branches, agent banking, and digital banking services. The number and usage of these channels have been increasing steadily which enhances financial inclusion.

Banks’ Branch Network

In 2022, the total number of bank branches and ATMs fell to 987 from 990 in 2021. Large banks accounted for 55.2% of the branch network.

Urban centers accounted for 51.6% of total branches. Most of the branches are located in the major cities of Dar es Salaam, Arusha, Mwanza, Moshi, and Dodoma.

Banking Agents

In 2013, BOT introduced comprehensive agent banking guidelines that permit licensed banks and financial institutions to appoint retail agents for their banking services. This provides a mechanism through which banks can profitably extend their services to previously unbanked lower-income individuals.

The agent banking business has grown regularly since then in the number of agents, number of transactions, and value of deposit and withdrawal transactions. In 2022, the total number of bank agents increased by 53% to 75,238 from 48,923 in 2021.

Deposits through agents increased by 71.1% to TZS 61,915.9 billion. The growth implies that this service delivery channel has become a more effective means of mobilizing deposits and increasing access to and usage of banking services.

The agent banking business is dominated by large banks which accounted for 59.7%. Urban centers accounted for 56.5% of total operating bank agents.

Mobile Money

Mobile Money, also known as “M-Pesa”, was introduced in Tanzania in 2008. The service, provided by mobile network operators (MNOs), allows users to deposit, withdraw, transfer money, and pay for goods and services, but also access credit and savings, and more recently insurance and investment services, all with a simple mobile device via SMS.

Already in 2007, BOT through the 2007 Electronic Payment Systems Guideline created new rules for electronic payment schemes allowing non-bank financial institutions to offer electronic payment schemes and money transfers. Although it did not accommodate mobile money, it opened the doors for MNOs to offer money transfer and payment services.

Since the law did not address the licensing of MNOs, operators were required by BOT to apply for Letters of No Objection in conjunction with a bank to conduct payment services legally.

Realizing the potential of alternative payment instruments improving access to, and adoption of formal financial services, eventually increasing financial inclusion, BOT issued the first letters of no objection to the first MNOs launching mobile money in Tanzania in 2008.

As the market has continued to develop more MNOs launched mobile money services, BOT made concerted efforts to find a legal and regulatory framework that would provide sufficient legal certainty and consistency to support a stable mobile money market, promote financial inclusion, and protect customers.

In 2015, BOT introduced a number of regulations for the mobile money and payment systems. These allowed for interoperability between MNOs, for money to be transferred from bank accounts to mobile money accounts, and for banks to give small-scale loans via mobile platforms.

In 2016, Tanzania became the first country in the world to achieve full mobile money interoperability. Today, Tanzania is one of the most advanced mobile money markets in Sub-Saharan Africa.

By 2022, mobile money active subscriptions reached 38,338,776 out of 60,192,331 mobile subscriptions and a population of 61,741,120 of which the adult population (aged >14 years of age) is 35,341,132.

Such high mobile network and mobile money penetration have greatly impacted the bank’s network strategy to reach the unbanked population and increase financial inclusion. Today, mobile money technology is firmly considered the key enabler for accelerating financial services access for marginalized communities, particularly low-income individuals, small enterprise operators, and smallholder farmers.

Abdulmajid Nsekela CEO & MD of CRDB, Tanzania’s largest bank with a network of 260 branches throughout the country, is clear that physical presence is no longer a determinant in the adoption of financial services: “With improved technologies and connectivity, banks are increasingly providing services via cellular networks and the internet, which then provides an opportunity for inclusion beyond the traditional brick-and-mortar models.”

Financial inclusion is receiving an additional boost as BOT continues to implement the Tanzania Instant Payment System (TIPS), a national switch for retail payments launched in August 2021.

TIPS enhances the efficiency of processing retail transactions among participants by reducing the obstacles associated with bilateral interoperability agreements. This enables interoperability between banks and non-banks, including e-money issuers, allowing users to send and receive money in real time using mobile phones or bank accounts

Moreover, TIPS reduces the usage of cash, enhances transparency, fosters a level playing field for innovation and competition, and promotes financial inclusion by reducing the costs of interoperable transactions.

In March 2024, the Bank of Tanzania (BOT) announced that it has incorporated all payment service providers into TIPS, confirming its commitment to making financial transactions quicker and more affordable.

A use case of TIPS indicates that an average of 400,000 transactions, valued at TZS 20 billion, are processed per day.

Credit Reference Bureaus

Credit reference bureaus play a critical role in increasing lending activity and access to capital, and in turn, accompanying economic growth by assisting lenders to make faster and more accurate credit decisions.

Tanzania passed the credit bureaus regulation in December 2012, and in 2013 BOT licensed two credit bureaus: CreditInfo, and Dun & Bradstreet. These institutions are responsible for collecting, analyzing, and providing credit information to different lending stakeholders, thereby facilitating the credit underwriting process.

In its Annual Report 2022-2023, BOT stresses that improved asset quality of the banking system is ascribed to the usage of credit reference bureau services. This is why BOT continues to sensitize banks and financial institutions to the importance of sharing accurate credit information and usage of credit reference bureau services to reduce information asymmetry in credit underwriting processes, reduce the level of NPLs, and support the growth of credit to the private sector. During the year under review, the number of non-regulated institutions that shared credit information with the bureaus increased to 118 from 114 in the preceding year, with credit inquiries scaling up by 182.3% to 10,375,696.

Islamic Banking

Islamic banking, or Sharia-compliant banking, refers to all banking activities, part of the wider Islamic finance, that comply with the Islamic law (Sharia) that contains the rules by which the Muslim world is governed. Although Islamic banking is not restricted to Muslims, clients must accept the ethical restrictions underscored by Islamic values.

Tanzania’s population of 62 million is about 34% Muslim. Tanzania is still in the early stages of adopting Islamic finance, with only one fully-fledged Islamic bank: Amana Bank. The bank started its operations in 2011 and primarily offers Shariah-compliant financial products.

Since then, a few other commercial banks have started offering Islamic financial services, namely Azania, CRDB, KCB, NBC, and PBZ. And in April 2024, TCB Bank announced it started preparations to introduce banking services according to Islamic Sharia by the end of the year.

According to Mohamed Issa, Chairman of Yusra Sukuk Company, Tanzania’s first Islamic brokerage and investment advisory firm, there is a huge latent demand in Tanzania for Islamic financial services (banking, bonds, Takaful insurance).

The main concern with respect to Islamic banking in Tanzania is that there is currently no specific legal framework to cater for it as well as resolving legal disputes arising from it. The sector is governed by me same regulations as conventional banking and these do not actively accommodate Shariah-compliant banking, hence banks are not able to introduce Islamic products that the existing legislation does not cover.

With appropriate regulations and partnerships, Islamic finance can channel significant global funds into Tanzania’s priority sectors like infrastructure, agriculture, and SMEs.

In this regard, in early 2022 BOT formed the Islamic Banking and Finance (IBF) technical team, which was tasked to spearhead the exercise of developing and implementing the framework for Islamic Banking and Finance.

In January 2023, BOT requested proposals and recommendations from different Islamic Banking and Finance stakeholders on legal and regulatory changes that will make Islamic Banking and Finance more feasible in Tanzania.

Governor Tutuba expects that by June 2024, the Prudential Regulations, Guidelines and Circulars on Islamic Banking and Finance will be issued. These will, among others, provide guidance on the conduct of Islamic banking in Tanzania as well as the handling of disputes arising from Islamic banking.